Matt Orlando likes to talk about trash. This is unusual for a chef with his resume; after all, the Californian has worked in restaurants whose names melt on the tongue of any gourmet. In Manhattan, he cooked at Le Bernardin and in England at The Fat Duck. More recently, he headed the kitchen in René Redzepi’s Noma , perhaps the best restaurant in the world. People come from far and wide to eat what Matt Orlando cooks.

Image: Amass

However, since venturing out on his own with Amass, he has been developing his dishes based on the waste caused when preparing them. For the energetic chef, never having any leftovers has become a sport in which he and his team are using to spur themselves to top performance. They dry apple peels and serve them as tea. They conjure up dumplings from ground fish bones. They combine the ice water from wine coolers and tap water left behind by guests and use them to water the restaurant garden. They even melt down the candle stubs left over on the tables and make new candles out of them. All of this takes time, which is always a scarce commodity in top gastronomy. But Orlando is proud of this investment.

Image: Amass

Cooking with responsibility

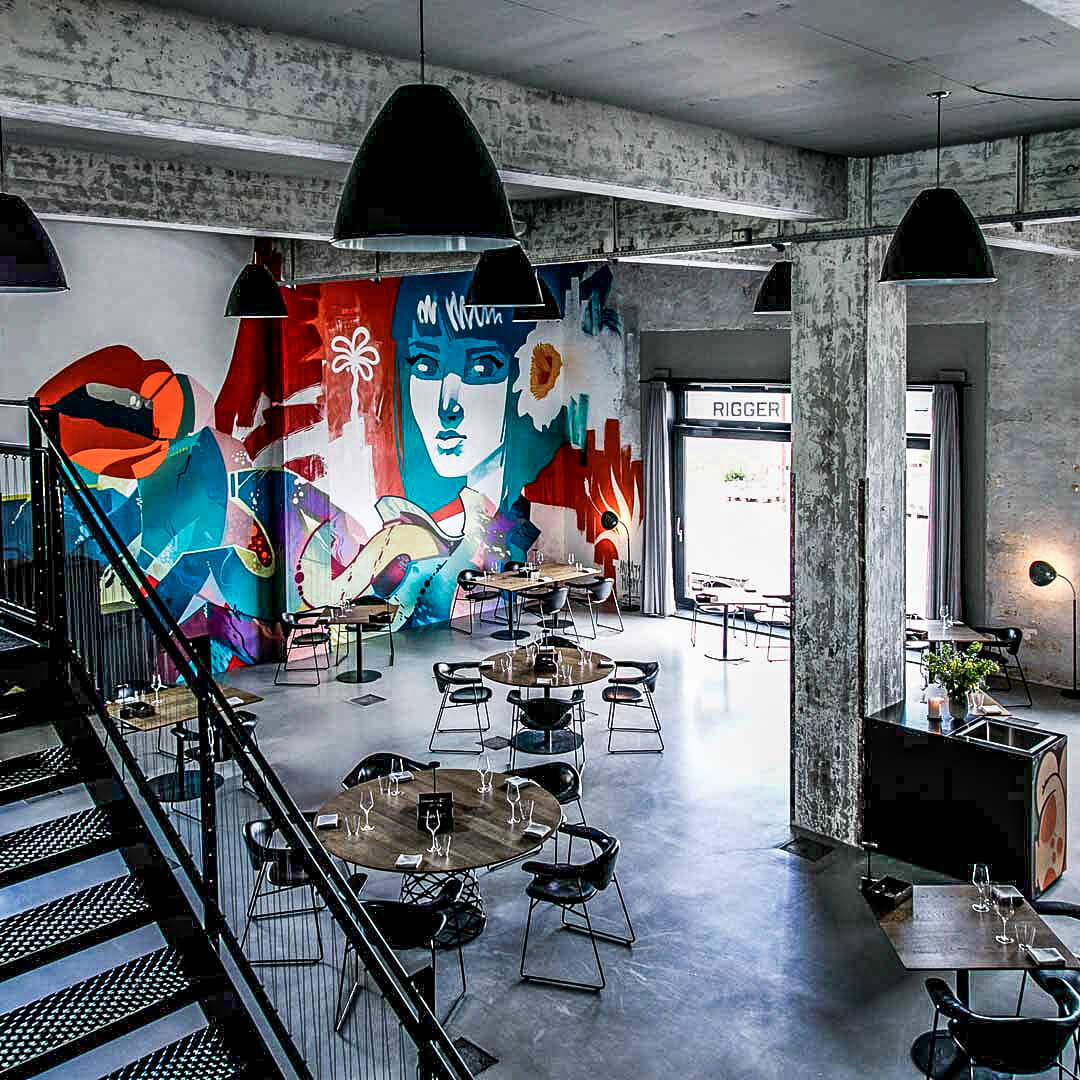

He and his wife, Julie Bergstrom Orlando of Denmark – they met at Noma and she now manages Amass – were looking for a location to take the next step in their careers. The two found it in what was still a rough part of Copenhagen’s harbor at the time, on the Refshaleøen peninsula, surrounded by water and shipyards. Even for the fine dining metropolis that is Copenhagen, Amass was an exciting new addition at the time. In 2013, the daily Danish newspaper Berlingske reported on the opening of what it called “the greatest international interest in a new Danish restaurant” ever. However, the man who attracted this interest felt he had not yet arrived. “As a chef for someone else, you are intently focused on delivering exactly what that person wants, down to the last detail.” This limited his own personal vision. He used Amass’s first three-week winter break to do some soul-searching – and it brought him back to his roots.

Image: Amass

Matt Orlando grew up in San Diego, California. His parents – who were “real hippies” – went surfing and camping with him. The family moved around a lot, he says. “But no matter what little beach hut we lived in at the time we always had a garden – and composting was always a part of it.” He remembered this when he tipped leftover food into the compost pile in the garden of his newly opened restaurant. “That environmental consciousness, the appreciation for nature that my parents had given me, was suddenly back.” He gathered his team around him and, as he tells it, gave a fiery, impassioned speech.

Since then, the question that precedes every decision has been: Are we dealing with resources, the environment and each other responsibly? If not, what can we do differently?

Image: Amass

Sustainability as a vision

Approximately eight per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions are estimated to be from cultivating food, which is later thrown away. “Our food system is messed up in many ways,” says Orlando. Sustainability is his guiding star. Nearly 100 percent of the products used in Amass come from Danish organic farmers or suppliers. The restaurant gets its fish from local waters and sustainable fishing. They only serve meat in small quantities – Orlando’s parents only let him meat once he was 13 years old – and it has to come from ethical sources.

However, Orlando is so determined to pursue his vision that it has already developed a momentum of its own that extends beyond the kitchen. It bothered him that the table linen manufacturer delivered their goods wrapped in plastic, so they worked together to find an alternative. The supplier now wraps the linens in old table cloths and retrieves them when they make the next delivery. And they don’t just do this for Amass. “They now supply a number of restaurants in the city this way. It saves them money, and it spares us the plastic.”

Not all producers are as cooperative. Orlando wanted to source reusable transport cases for one of his suppliers who packed their vegetables in plastic. The company refused – the logistics were too much. “We are no longer working with them,” says Orlando.

Image: Amass

Conserve resources – impress with taste

Just a few steps away from the kitchen at Amass, the restaurant garden is made up of nearly 9700 square feet of meadow, which are covered with wooden raised beds. Sitting here with a drink, you can look across the water and see the Little Mermaid statue on the other side of the harbor. Flowering and ranked or strawy and bare, the beds in front of the windows remind restaurant guests that every season tastes different. For the employees, the garden is a school of taste and a field of experimentation. “This is where we get to know the entire life cycle of our plants. When we order them from the farmers, it is always just a snapshot of what is to come.” This is how the idea of developing dishes based on their waste came about.

For example, Matt Orlando starts with a pumpkin’s hard outer shell, which he roasts until it becomes soft and turns black. After transforming the amino acids into sugars, he serves them as a dark mash seasoned with pumpkin miso. He ferments the seeds and stringy insides in brine, processes them into a sweet and sour powder and oil and seasons the softened, steamed pumpkin mash with both. The path is using the complete pumpkin. Most guests know that some of the skillfully arranged courses on their €160 menu consist of ingredients they would throw out in their own kitchens.

Image: Amass

Since opening, the restaurant’s waste volume has decreased by 75 percent and water consumption by around 1374 gallons per year. However, for Matt Orlando this is not enough; he also wants to pass on his experience. In the test kitchen, he and his team have been dehydrating, rubbing, burning or steaming leftovers such as kale gel or lemon skin for years to find out which ingredients can be made from them. “We know how to make something delicious from leftovers.” During the pandemic, he set up a research space where he now invites food producers to collaborate.

Their waste should be turned into new delicious products. The first triumph from this venture is a sourdough caramel ice cream bar with chocolate coating, which was made in cooperation with the industrial bakery Jalm&B and the ice cream manufacturer Hansens. The basis is stale bread, which is turned into syrup and then mixed with milk. 772 pounds of bread were transformed into 15,500 ice cream bars – the first large-scale production for Amass and also the first impact it made on the supermarket shelves. The ice cream bars sold so well that Jalm&B wants to produce 150,000 more next year. Amass is earning a little bit from each of them.

Image: Amass

Sustainable gastronomy – without fences

Matt Orlando knows that a fine-dining restaurant doesn’t generate a lot of revenue. One of his former bosses gave his some advice: If you want to be rich, open a pizza shop. “The cost of having a high-end restaurant is insane,” says Orlando. “We don’t charge as much for food as we should. But we don’t lose any money with Amass either.” In the end, acting responsibly can also mean operating sustainably. The garden, for example, can only produce around ten percent of what the kitchen needs, says Matt Orlando. “That’s why we cultivate the ingredients there that we would otherwise have to buy at a high cost, like flowers, sprouts, cabbage and berries. This saves us a lot of money.” Nevertheless, the area is not fenced in. Orlando considers it a community resort for guests and neighbors. School children are also allowed to drop in and garden with him and the Amass team as part of the Amass Green Kids Program.

In this way, he passes on what he has learned from his parents. His mother just visited for the first time in 20 months. He guided her through the restaurant and garden and answered her many questions. “We were here all by ourselves. When I told her that she and my father were the inspiration for all of this, tears came to her eyes.”

Image: Amass