Here’s another example: When baking bread, the pleasant scent of fresh, golden-brown bread fills the entire kitchen immediately after opening the cooking system door. Whose mouth doesn’t start watering when they smell this? It might seem almost like a magic trick that RATIONAL cooking systems, among others, have mastered to perfection, and yet the question we still ask ourselves is this: What exactly is happening here?

To understand this, we need to take a look at the chemistry and molecules involved.

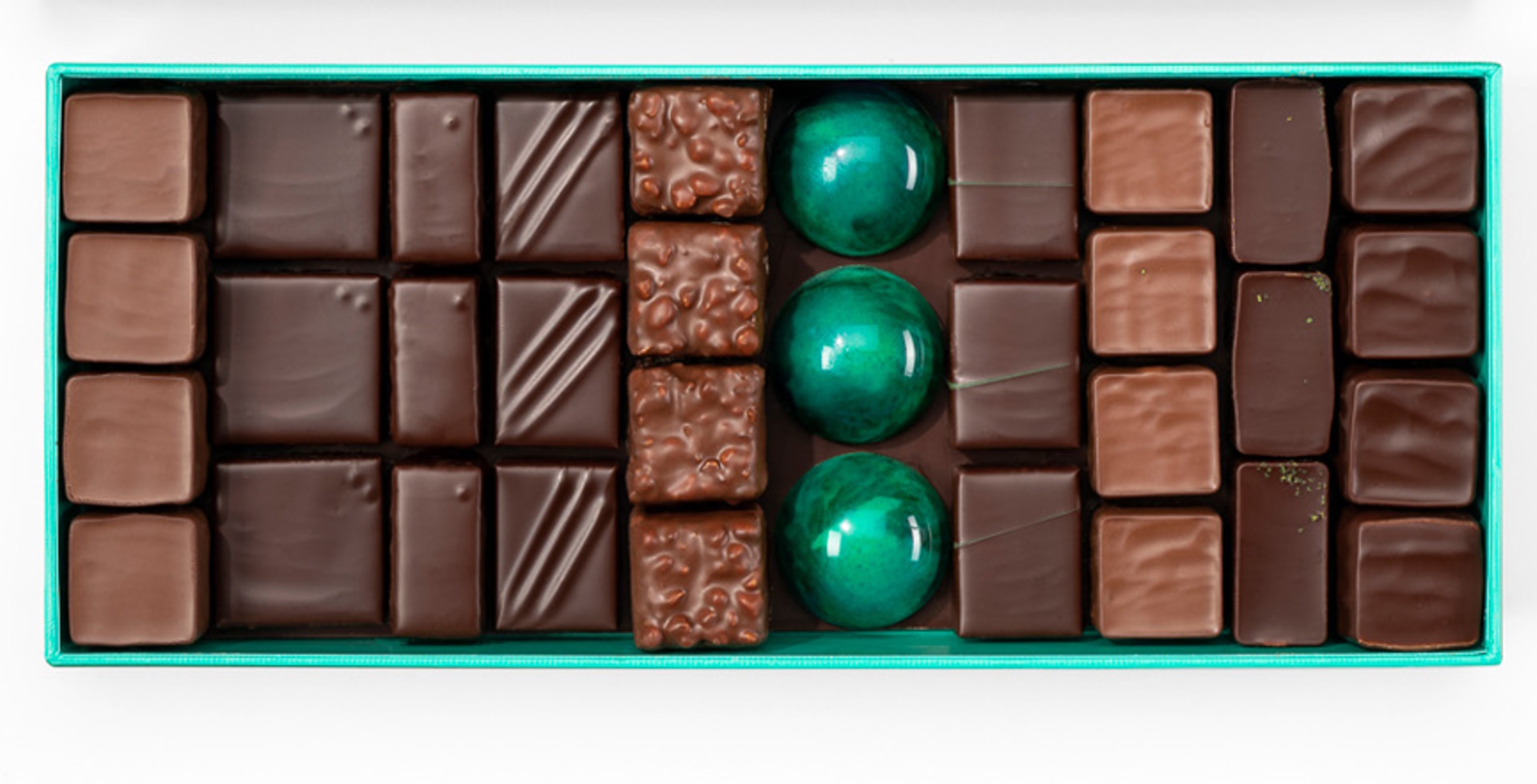

Image: Rational

Sugar and amino acids – a productive encounter

Among other things, sugars and amino acids, are found on the surface of meat and bread dough – not to mention coffee beans or some vegetables – and their special feature is that they with each other in a very reactive manner. Their love is quite productive, since hundreds of molecules are born a few minutes after they meet.

Some are fleeting and fragrant and can be sensed throughout the kitchen. Others are only released while chewing and are responsible for that typical roasted taste, while the third, colored molecules, explain those familiar grill marks, among other things. By the way, did you know adult like roasted flavors more than children do?

Image: AdobeStock | nikolaydonetsk

Discoverer of the reaction

This reaction, which applies to the taste and flavors in cooking, is called the Maillard reaction. It was named after the French scientist Louis Camille Maillard, who conducted research in this field in the early 20th century. Although many scientists have studied the reaction since then, some of its aspects remain mysterious. However, we can be sure that it involves several complex chemical processes that take place without any enzyme activity.

Influencing factors of the Maillard reaction

It is known that the speed of the reaction is determined by the temperature and time – it even takes place in champagne, albeit extremely slowly. The higher the temperature, the faster the reaction and hence the characteristic dark coloration and development of the flavors described above.

Image: Rational

The reaction is also more significant at an alkaline pH value, therefore soda is used for pretzel dough or to make a better dulce de leche. Another factor is humidity, which is why the food must not be too moist or too dry to achieve a perfect result.

Unwanted Maillard reaction

When the temperature exceeds 248° F and some water is present, an undesirable Maillard reaction can also occur in baked goods or when deep-frying foods that contain a lot of carbohydrates. Among other things, this can produce the harmful substance acrylamide. To avoid this, it is recommended not to deep-fry above 338°F.

Image: AdobeStock | Nestor

As you can see, obtaining those perfect roasted aromas, flavors and colors is a science in itself. Luckily, RATIONAL users have one of the best experts in this field at their side: the iCombi guarantees a perfect Maillard reaction every time.

Thank you to Dr. Grégory Schmauch and the RATIONAL Cooking Research team for giving us an exciting insight into this topic!