Take milk, cream, sugar, and an egg yolk, mix them all together, and stick them in the freezer. After a few hours, you wind up with… a rock-hard, grainy disaster. Okay, now do it again, but stir the mixture constantly as it freezes (with an ice-cream maker, for example). Hey, look at that! Congratulations! You’ve got creamy, velvety-smooth ice cream that melts in your mouth just the way you’d expect.

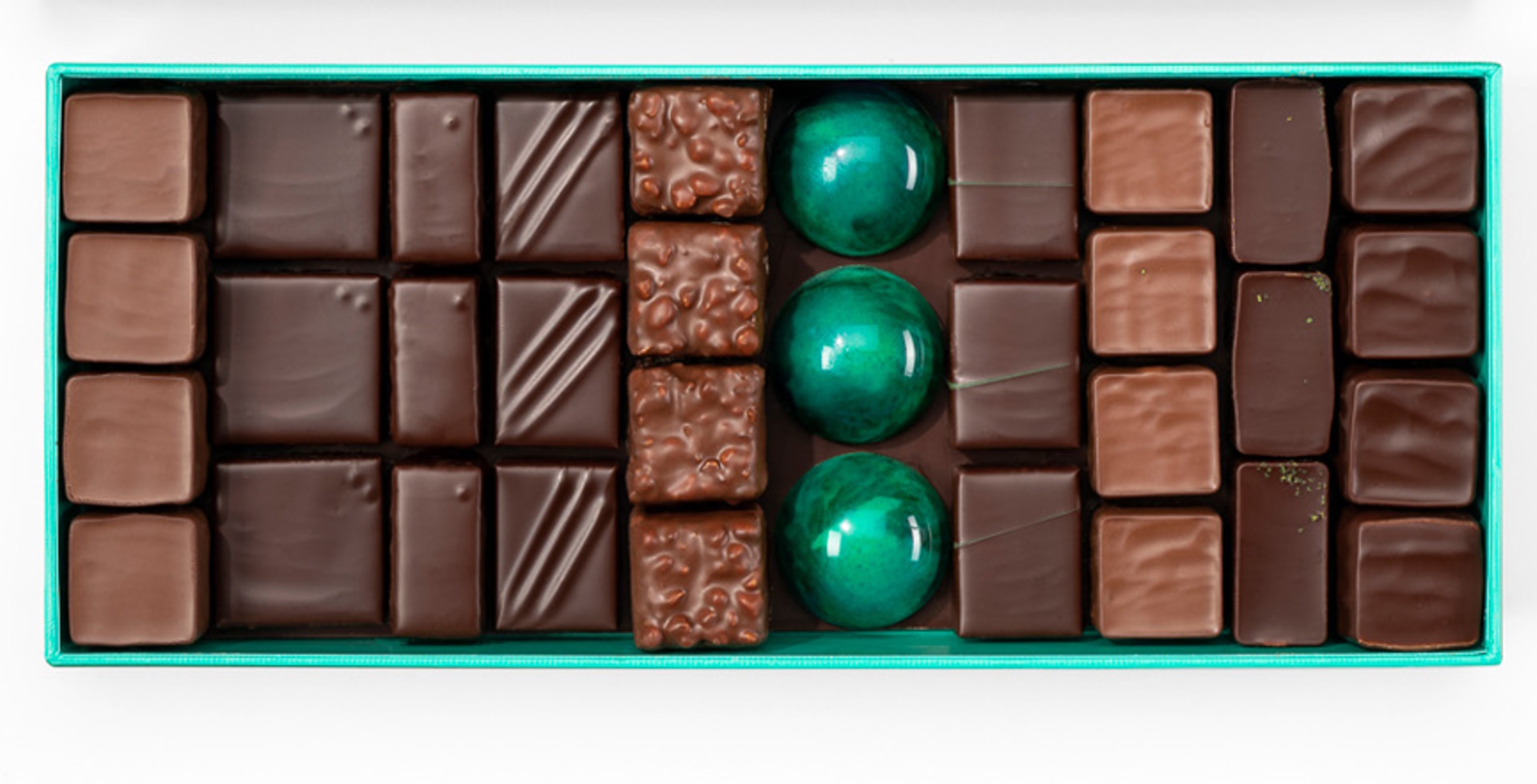

Image: Woop Woop IceCream

Stirred. Not shaken.

In both cases, the mixture starts freezing where it’s coldest, aka near the edges of the container. Water crystallizes as it freezes, and then those small individual crystals slowly grow together, forming a solid structure like an ice cube… or that milky mess from the first example. In the second example, the crystals form as well, but the ice-cream maker paddles continuously “scrape” them off the edges of the container and stir them into the mix. They also incorporate air, which the fat molecules quickly trap and stabilize.

Sieh dir diesen Beitrag auf Instagram an

Now we’ve got a thick, viscous matrix of fat and sugar water. Once everything gets too viscous to stir (which happens when around half the water is liquid), it will simply continue to solidify. So basically, ice cream is a colloid of ice crystals, a nearly-solid mixture of fat and sugar water, and fat-stabilized air.

Crystal size determines mouthfeel

The ice cream’s texture is directly related to the size of the ice crystals: the smaller the crystals, the softer and more velvety the ice cream. In order to keep the crystals small, the crystallization process has to happen fast. That way, crystals form throughout the mixture, but they never have time to grow. The key is to chill the matrix as quickly as possible. But how?

Chemists have found a solution: liquid nitrogen. When liquid nitrogen is mixed into the matrix, the temperature immediately drops to -196°C (-320°F), which means instant freezing and super-small crystals (along with an impressive fog-machine effect). Some specialty ice cream parlors, such as Whoop Whoop in Berlin and Dr. Ice Cream in Hamburg, have started making ice cream using liquid nitrogen.

Making ice cream with liquid nitrogen.

Image: Woop Woop IceCream

You’ve probably already noticed that air is one of ice cream’s most essential “ingredients.” A few ice cream manufacturers have started taking advantage of this, using air as a simple (and, more importantly, cheap) way of adding volume to their products. Some discount ice cream products contain as much as 50% air!

Ice cream: fresh from the combi-steamer?

Heating ice cream in an iCombi? Ridiculous, right? Not at all! As long as the ice cream’s packed in a heat-insulating “container,” you’ve got nothing to worry about. And if that container just happens to be edible (say, a meringue dome with a sponge-cake base), the result is an amazing dessert: Baked Alaska (also known as Omelette Surprise in German or Omelet Norvégienne in French).

Image: ShutterStock | Anna Shepulova

Thanks to Dr Grégory Schmauch and RATIONAL’s Cooking Research Team for these ice-cold insights!